The first restoration project under the FIP occurred in summer 2024, at The Wetland Conservancy’s Starr Creek Preserve, located along Alsea Bay. Restoration actions included removal of invasive plants, secure placement of large woody debris both instream and throughout the floodplain, and seeding/planting of native vegetation at appropriate elevations to restore tidal marsh, scrub/shrub, and spruce swamp habitats. These actions will improve tidal wetland habitat for coho and Chinook salmon, steelhead, and other fish and wildlife species, while also helping add resilience to climate change and sea level rise. More than 90% of forested tidal swamps have been lost from Oregon estuaries. Wood placed throughout this site will provide essential cover for fish and invertebrate species, protection from currents, and foraging opportunities, while also creating nurse logs and elevated platforms to support the growth of Stika spruce, Pacific crabapple, willow, and other scrub/shrub species. Logs placed instream will help collect sediment, slow and spread water over the floodplain, and could even encourage beaver to return to this site, coupled with establishment of enough native plants to support them.

Bayview Oxbow

The Bayview Oxbow is located on the northern end of Alsea Bay where historical tidal wetlands once thrived. Efforts to restore these wetlands have been in the works for years and aim to reconnect the oxbow with Alsea Bay so that water can flow over the natural floodplain once again. The Wetlands Conservancy, which owns most of the western portion of the Bayview Oxbow, completed preliminary designs for restoration at Bayview Oxbow in 2019 in coordination with adjacent landowners and other stakeholders.

Currently, these designs have been picked up by the Oregon Central Coast Estuary Collaborative (OCCEC) which will be conducting a thorough technical review of culvert removal and bridge replacement in coordination with Lincoln County and partners. The Bayview Oxbow has been identified by OCCEC as a Focused Investment Partnership (FIP) project site and will receive a holistic approach to reconnect the oxbow and address infrastructural concerns with the larger goal of increasing resilience to sea level rise and other climate change impacts.

The Bayview Oxbow used to consist of extensive tidal wetlands, with tidal flows traveling into the oxbow during high tide and flowing out during low tide. This regime has been dramatically altered by dikes, tidegates, and other infrastructure. There were also spots within the oxbow complex that have been identified as historical forested swamp habitat, a once abundant wetland type along the Oregon Coast. In the past 150 years of land use, these wetlands have been converted for agriculture and industry.

1939 aerial image of the Bayview Oxbow referenced in text below.

The earliest photos of the Bayview Oxbow from 1939 show the site already diked, ditched, and utilized by early settlers. Land use priorities have contributed significantly to the decline of wetland habitat along the Oregon Coast; tidal wetlands declining by an average of about 60% and forested and scrub-shrub swamp by an average of about 95% since European settlement. Addressing these massive changes in wetland composition along the Oregon Coast is necessary to restore natural ecosystem processes that have been deeply disturbed by human land use.

In the next few years, project partners expect to begin restoration actions in response to a comprehensive project design. Utilizing a variety of grant sources and collaboration with a host of partners, the Bayview Oxbow restoration project aims to reconnect the oxbow with the Alsea Bay, promoting wetland wildlife and generating community resilience to projected sea level rise in line with landowner interests and concerns.

Lint Slough

Lint Slough has been the site of Midcoast-involved restoration work since 1998 with goals of restoring tidal interaction with Alsea Bay. Since, Midcoast and partners have removed water controlling infrastructure, such as dikes and dams, restoring tidal access and promoting the establishment of historical wetland habitat.

The first restoration projects along the Lint Slough were motivated by the lasting impacts of a salmon rearing facility which proved a lasting barrier to tidal interaction even after it was discontinued in 1972. To restore the natural flow of Alsea Bay tides into the slough, Midcoast and partners removed various instream infrastructure that was left from the facility.

While early projects at this site succeeded in reconnecting historical wetland habitat and tidal influences, there still remain barriers to fish passage and even more habitat upstream to be reconnected.

While lower portions of the Lint Slough area have been restored, further opportunities exist upstream and are being explored by MidCoast and our partners in the Oregon Central Coast Estuary Collaborative (OCCEC) within the Focused Investment Partnership (FIP) “Restoring Resilience to Two Estuaries.” A majority of these upstream areas are ranked high or medium-high in MCWC's Landward Migration Zone study, making them targets for work now to build resilience to sea level rise and climate change, preparing them to be future tidal wetlands.

Early project partners include USFWS, ODFW, City of Waldport, and USFS.

Echo Mountain Fire

In September, 2020, the Echo Mountain Fires burned through the town of Otis, Oregon and the surrounding area. As a result, about 300 homes were destroyed and the natural landscape suffered from hazardous materials such as ash, soil instability, and invasive plants. Removal of hazardous materials and standing dead trees after the disaster was accomplished by FEMA, EPA, ODOT, and Pacific Corps.

To stabilize soils, manage invasive vegetation, and provide long-term protection for water systems, the Salmon Drift Watershed Council, now incorporated into MidCoast Watersheds Council (MCWC), and partners did plantings on 18 acres in the Echo Mountain Fire zone and salvaged logs for future restoration projects.

Restoration site prior to planting taken in April, 2021 (left) and after planting taken in May, 2021 (right).

Example of fire-damaged trees salvaged for restoration projects.

Sites were selected for their vulnerability to erosion and water system contamination in the context of drinking sources and aquatic species health.

Continued in 2022 and 2023 by MCWC and partners, further riparian and upland plantings, and weeding occurred to reduce erosion and water system contamination. The project is still ongoing and has prioritized site preparation and invasive species management so far.

Project partners include Lincoln Soil and Water Conservation District, the Natural Resources Conservation Service, the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians, and Landscaping with Love.

Pixieland/Tamara Quays

Pixieland and Tamara Quays are areas where human influence has significantly altered natural ecosystem processes and vegetation. Both sites are now under ownership of the Siuslaw National Forest and have been managed with restoration as a primary goal. Years of restoration work and monitoring by the Salmon Drift Creek Watershed Council, now integrated into MCWC, and the U.S. Forest Services have removed invasive vegetation and promoted native plant growth, restored hydrology via reconnected tidal channels, and restored ecosystem processes in these historic estuary habitats.

To learn more about this series of projects, check out the project summaries below:

Project partners include USFS Siuslaw National Forest, Oregon Department of State Lands, ODOT, and USFWS.

Lower Drift Estuary

Regrowing lost habitats

Drift Creek flows into the Siletz Bay just south of Lincoln City, where it forms a beautiful estuary habitat. The area is now part of the Siletz Bay National Wildlife Refuge, but the habitat has been severely degraded in the last 150 years. Several partners are restoring the wetland’s natural functions by removing tidal flow restrictions, digging new channels for the tides to flow through, and promoting native plants.

The Lower Drift project aims to restore roughly 40 acres of tidal wetlands in 2023 through the removal of dikes, restructuring and connecting of tidal channels, creating small mounds and planting native species, placement of large woody debris (LWD), and controlling invasive species. An additional 40 acres will be restored in 2024. These restoration efforts added to 86 acres of previously restored wetlands within Siletz Bay National Wildlife Refuge.

The value of estuaries’ ecosystem functions have not been prioritized in recent history. Instead, Oregon’s tidal wetlands have been diked, ditched, developed, or grazed to the point that the area of Oregon’s tidal wetlands has declined by an average of about 60%.

Once a common habitat along the Oregon Coast, forested swamps have declined by an average of roughly 95%. New research shows that forested swamps provide important ecosystem services such as shelter and foraging grounds for salmonids, multi-layered wildlife habitat and stream shading, and high levels of carbon storage in the soil.

-

Wetlands are areas where water covers the soil, or remains close to the surface all or most of the year. Both marshes and swamps are types of wetlands. Marshes are wetlands that are dominated by soft-stemmed plants such as grasses. Swamps are wetlands that are dominated by woody plants such as trees or shrubs.

A forested tidal swamp (Photo by Laura Brophy)

In addition to directly supporting the preservation of estuary wildlife, the Lower Drift project plays a part in strengthening Oregon’s coastal climate change resiliency. Estuaries have a built-in system to adapt to rising sea levels. As sediment flows into the estuaries from the tides and river, it collects in vegetation and increases the elevation of the wetlands. Estuaries are also “blue carbon” ecosystems (such as mangrove forests and seagrass beds) which are even more efficient at storing carbon from the atmosphere than tropical forests!

How?

-

Improving topographic diversity higher elevation spots for spruce and native shrubs are present.

Placing LWD to create potential nurse logs.

Planting of spruce and native shrubs and managing invasive species.

-

Removing tidal flow barriers such as old dikes, culverts, and riprap to allow for natural deposition of sediment.

Placing of LWD to aid in catching of sediment.

Creating elevation gradient to promote sediment deposition.

-

Increasing tidal channel connectivity through channel shaping and removal of tidal flow barriers.

Placing of LWD to create shelter for aquatic species and coastal birds alike.

Planting of native plants.

The first phase of the Lower Drift restoration began the summer of 2023 when stream diversion and fish salvage took place in July prior to the restructuring of tidal channels using large machinery. During fish salvage, species such as shiner perch, greenling, rockfish, gunnel, stickleback, and Coho salmon were successfully salvaged from the active work area and safely moved to habitat downstream.

Project partners include US Fish and Wildlife Service, Oregon Coast National Wildlife Refuge Complex, US Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, private landowners, the Lincoln Soil and Water Conservation District, the Wild Salmon Center, National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, and the Confederated Tribes of the Siletz Indians.

To learn more check out these resources:

Beaver Creek

A Basin Wide Effort

Near Seal Rock, Oregon, the ocean tributary Beaver Creek provides year-round habitat for endangered Oregon Coast coho salmon, as well as Chinook, winter steelhead, and other fish. Stretching from its headwaters in protected old growth forests to Ona Beach where it flows into the sea, the Beaver Creek watershed covers 21,532 acres and 42 miles of stream habitat. Despite harboring one of the healthiest existing coho salmon populations in the Midcoast region, it has been subject to extensive human alteration that reduced fish habitat over the last 100 years. MCWC has been working with a diverse group of partners to improve habitat in this basin through riparian planting, Large Woody Debris (LWD) placements, and reestablishing complex streams.

Michael and Sharon

Michael, MCWC Administrative Board Member, and Sharon live near South Beaver Creek where they enjoy wildlife watching and doing restorative home projects.

As is the case for many of Oregon’s coastal streams, North and South Beaver Creeks were converted for agricultural practices and simplified to best suit crop production. Areas “over by 101 [were] covered in fields, you know, it was pastureland.” says long-term resident and MCWC Administrative Board Member Michael Meagher. Many people in the area still derive livelihoods and family practices from agriculture.

Segments of lower North and South Beaver Creek and their riparian zones are now part of the Brian Booth State Park. The acquisition of the land occurred from 2007 to 2009, private parcels being purchased with roughly $1.3 million in Lottery dollars and $400,000 from the USFWS Coastal Wetland grant. The headwaters reside in the protected Siuslaw National Forest, and private lands are settled between this management region and the protected stream mouth at Ona Beach. Private landowners in the Beaver Creek Basin have been crucial to restoration efforts that Midcoast and partners have been involved in.

Kate

Kate, a long-term MCWC volunteer, has lived along the North Beaver Creek for 51 years and is passionate about having conversations on the importance of protecting natural processes and wildlife.

Kate Scannell, who moved to her current property along North Beaver Creek in 1972, has been a dedicated volunteer with MCWC for years and recognizes that in order to have successful restoration, “You are going to need the cooperation of the landowners.”

While she has not collaborated with MCWC on her property, she’s implemented restoration on her own, volunteered with MCWC, and supported a backbone of trust within her community.

“In essence, once you get to know somebody, you also get to hear a bit of how they feel and you know, “I should think about that, you know I should see how I can help them see a way to keep our paradise the way it is.”

In collaboration with other organizations, people, and communities, MCWC has been slowly but surely completing restoration projects across the entire Beaver Creek Basin with a shared goal of protecting this space which is home to people and wildlife.

South Beaver Creek

Drone photo of the Beaver Creek Community site on South Beaver Creek during restoration.

This ongoing project has increased the complexity of a drainage channel artificially straightened for agricultural purposes. The previous drainage channel restricted the stream’s access to the smaller tributaries and seasonal floodplain. After restoration, the tributaries, freshwater wetland, and broad floodplain offer complex habitats for fish and aquatic organisms.

After removing about two acres of invasive Reed Canary Grass (RCG) by scraping with an excavator, the drainage ditch was filled in and the historic channel reconnected. LWD were placed in the new channel, and the scraped area was heavily seeded and replanted with native species.

The most recent restoration on the South Beaver Creek and neighboring streams has been dependent on collaboration from 7 private landowners. These properties, which lay between protected lands in the headwaters and downstream, are crucial to creating a mosaic of restoration projects throughout the South Beaver Creek water system.

North Beaver Creek

Claire and Eric

Claire and Eric have owned their North Beaver Creek property since 2000 where they have independently, and in collaboration with MCWC, restored the space through plantings and LWD placement.

This ongoing project seeks to address poor stream habitat on the privately-owned, low-gradient sections of North Beaver Creek to increase habitat value for coho salmon and other aquatic species from the headwaters to the mouth. Through a combination of work on protected public lands and private collaborators, the North Beaver Creek restoration project will help realize crucial coho rearing habitat and boost watershed-wide resilience.

When Claire Smith and Eric Horvath purchased their North Beaver Creek in 2000 they already had big plans to restore the area.

“We’ve planted western red cedar, Sitka spruce, and western hemlock, probably 2,000 of each,” says Eric, because the property had been a clear cut.

Through MCWC they were able to source many of those trees and in 2007 MCWC and partners placed LWD along their section of the North Beaver Creek to promote complex habitats. When we revisited the LWD placements this month, one of those logs placed in 2007 had been used by a beaver for their dam.

Beaver dam built on log placed in 2007 by MCWC and partners on Claire and Eric’s property. (photo taken on 08/18/2023)

The ongoing results of prioritizing environmental restoration on their property, such as seeing salmon populations grow, is something that Claire sees as potentially impactful across the community.

“. . . I feel like there are these things that are absolutely shared experiences that many many people have, like seeing the salmon in the water and it’s an experience that people really, really appreciate and, you know, look forward to.”

The ongoing restoration work by MCWC and partners on North Beaver Creek has already involved cooperation with multiple private landowners and collaborators such as Claire and Eric hope that projects such as theirs could increase visibility and interest in environmental restoration.

Shared goals

Private landowners have been key to the environmental restoration that has taken place across the Beaver Creek watershed so far. As MCWC and partners continue with the most recent projects, the cooperation of community members will not only create a wider area of land that has seen restoration actions, but will potentially strengthen the visibility of such work and connect people with resources that can assist restoration on their property.

In addition to the private landowners, project partners in this basin include The Wetlands Conservancy, Oregon Parks and Recreation Department, Seal Rock Water District, The Lincoln Soil and Water Conservation District, and the US Forest Service.

Poole Slough

Poole Slough is a tidally influenced channel in the lower reaches of Wright Creek, just before it flows into the Yaquina River Estuary.

Map of planting sites and road removal.

Poole Slough was dramatically simplified historically by removing large wood, building roads that are no longer in use, and the removal of wetland trees and shrubs. These actions reduced the quality and quantity of habitat for fish and wildlife.

1939 aerial photo showing simplified channel and now obsolete logging road

MCWC worked with partners to remove the obsolete road to allow full tidal exchange through the Slough, now owned by VanEck Forest Foundation and The Wetland Conservancy. This was paired with several large wood placements to increase channel complexity and encourage formation of side channels.

Excavator lowering road

Dumptruck removing fill

Water flowing freely over road at high tide

Our crews also planted spruce and crabapple along the slough to create scrub-shrub swamp habitat, over 90% of which has been lost along the Oregon Coast. These trees will provide large wood input to the slough long term.

Areas around Poole Slough were identified as future tidal wetlands when sea levels rise in our 2017 Landward Migration Zone study. To increase resiliency long term to climate change, large wood was placed in the areas identified. As they decompose, they will act as nurse logs for young spruce trees. In the meantime, they are habitat for birds, insects, mushrooms, and all the other beings that depend on fallen trees.

Partners include ODWF, VanEck Forest Foundation, ODFW, The Wetlands Conservancy, USFWS, The Forest Service, Pacific Forest Trust, and others.

Bummer Creek

Bummer Creek is located in the Alsea River watershed, and has been the target of numerous restoration projects since 2016. It was identified in an OWEB-funded Limiting Factors Analysis (LFA) as temperature and gravel limited. To address these issues, riparian planting, livestock exclusion fencing, culvert replacements and instream large woody debris placements have been implemented on a suite of 8 cooperating small private landowners within the basin.

Riparian plantings in protective cages with livestock fencing in background.

The LFA also classified the lower mainstem as highly incised and limited by reduced linkage to historical off channel rearing habitats. Both the USFWS and the MCWC have been instrumental in the development of salmonid accessible off channel wetland habitat in partnerships on the Parker property as part of this larger basin scale effort. LiDAR analysis has revealed the presence of 1.5 miles of diked and inaccessible oxbow habitat.

Map of channel alterations, wetland creation, and fencing on Bummer Creek.

We extended riparian fencing and planting downstream on Bummer Creek to the next 2 adjacent private land parcels (140 acres combined), reconfigured the wetland outlet to exit through its historical channel, and developed additional wetland habitats to store and retain winter runoff to address the summer temperature limitation in mainstem Bummer Creek.

This is a private landowner partnership with in-kind match contributed from Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQUIP) and Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program (CREP). Funds supported the creation of approximately 1500 feet of livestock exclusion fencing on the Jackson property, putting 7.7 acres of land into riparian reserve in 2018.

Little Lobster Creek

Warm water temperatures are detrimental, and can be fatal to juvenile salmon. Little Lobster Creek in the Alsea Basin is known to reach unsuitable temperatures. A lack of fallen logs in the stream from the days of homesteading lead to a loss of salmon spawing gravel, since high flows washed the subrtrate away without something in the creek to hold it there. MCWC worked with volunteers and partners to create long term solutions to these problems.

Cedar being planted in grazing exclosure in the riparian area

MCWC and partners (including a team of volunteers) reestablished native conifers in the riparian area for long term shade and wood recruitment to the stream, and placed a significant amount of large wood within the channel to trap migrating substrate in the spawning grounds. The Siuslaw Collaborative Watershed Restoration Program and Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board funded the implementation of this work and the project management, and a large match was also secured from the BLM through donating wood used in the project.

Big Creek

Big Creek is an ocean tributary flowing directly into the Pacific Ocean, about 10 miles south of the town of Yachats.

The site, now owned by Oregon Parks and Recreation Department (OPRD), was degraded by land clearing and grazing, removal of large wood from the stream, invasive plants, and unnatural fill in the floodplain. These actions greatly impacted instream complexity, floodplain and wetland connectivity, and riparian vegetation; all factors that limit Oregon Coast Coho (OCC) and other salmonid production.

This project improved instream, floodplain, and wetland function by removing introduced fill in 14 acres of floodplain, instream material placement to remedy channel incision, and placement of large woody debris.

Wood placement includes 10 instream log structures and over 200 pieces on the Big Creek floodplain. This increased large wood loading will further increase connectivity and side channel development over time.

Riparian planting and seeding will improve the functioning of the riparian zone and enhance a pollinator corridor between two known reproduction sites for the endangered Oregon silverspot butterfly.

Project partners include OPRD, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, US Forest Service, Siuslaw SWCD, Oregon Department of Transportation, and the Confederated Tribes of the Coos, Lower Umpqua and Siuslaw Indians.

Record Creek

Record Creek is a tributary to Swamp Creek, one of two major branches of the Bummer Creek sub-watershed within the greater South Fork Alsea system.

Riparian trees were historically cleared up to the stream, like many other areas in the Northwest. Eventually alders colonized the area, dominating the forest canopy and stalling later stages of forest from developing. While alders adequately provide the important function of shading the stream, their logs degrade quickly once fallen and do not contribute to creating the habitat complexity that fish and wildlife rely on to the degree that native conifers like Western red cedars do.

With funding from OWEB and log donations from BLM, in 2019 MCWC and placed 5 logjams over a 0.3 mile reach of Record Creek in order to trap and sort spawning gravel, form pools, and increase overall habitat complexity and floodplain connection. To provide an even longer term source of large woody debris to the stream, volunteers helped in planting 150 native Western red cedars in the alder-dominated riparian area of Record Creek. These trees will never be cut down, and will continue benefiting the habitat throughout their lifespan and beyond.

Ernest Creek

This project is located on the beautiful Thyme Garden property on Ernest Creek, a tributary of Crooked Creek in the Alsea River watershed which provides habitat for coho and Chinook salmon, cutthroat and steelhead trout, and lamprey species.

This project will improve stream complexity and riparian and aquatic habitat conditions by adding large wood structures and planting trees to supply wood for the stream long term. Current wood levels in the stream are significantly below ODFW recommended values, and has reduced complexity, floodplain connectivity, and increased channel erosion. Restoration work in 2002 reconnected Ernest Creek into its historical channel but experienced channel incision again because the lack of wood in the stream and soft, sandstone substrate.

MCWC and partners placed a total of 16 large wood structures on 0.7 stream miles, planted conifers on two acres of riparian habitat to increase potential for long term large wood recruitment, and . Project partners are Thyme Garden, another local landowner, Georgia Pacific, Northwest Oregon Restoration Partnership, and Bio-surveys LLC.

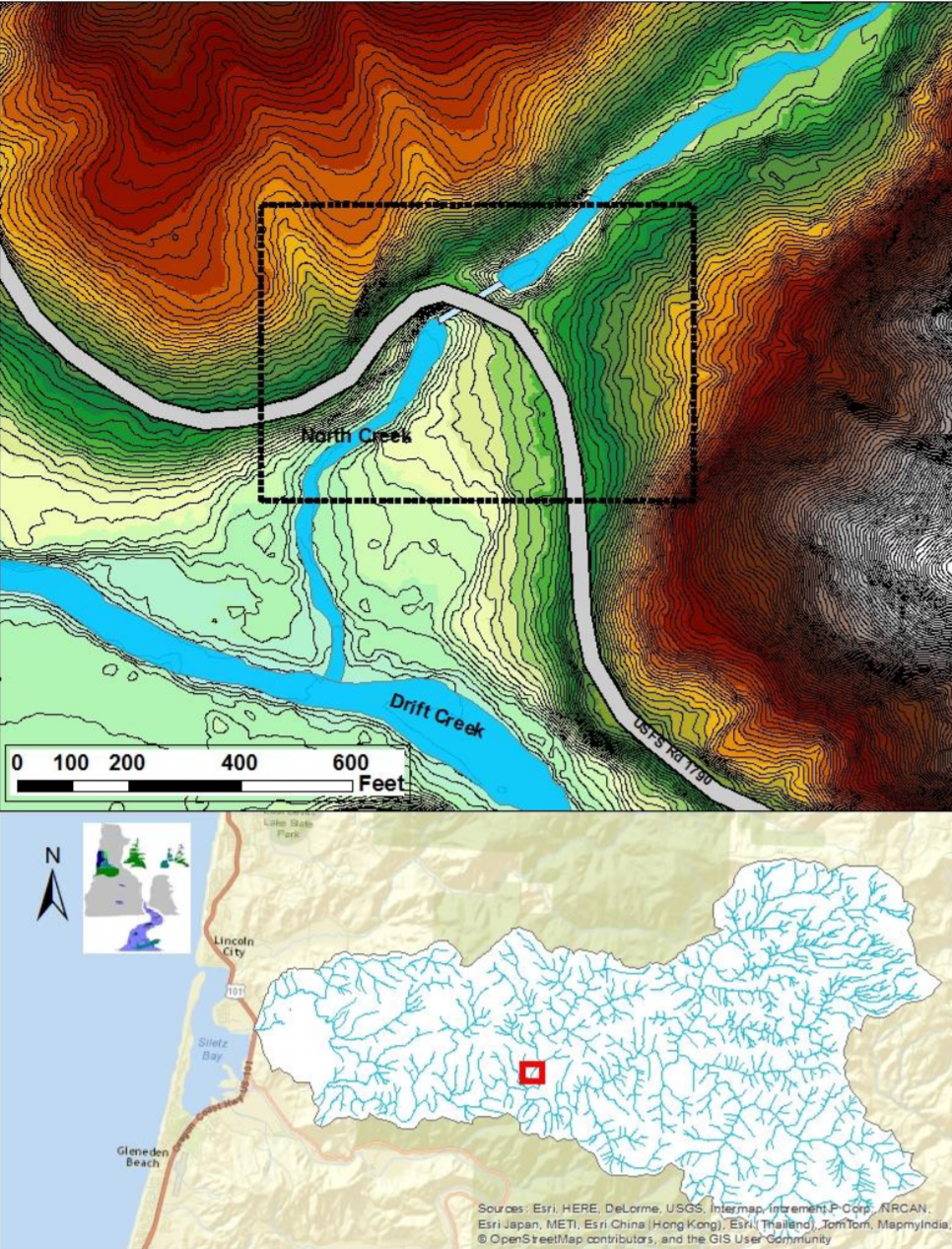

North Creek

Prime salmon habitat reconnected

In 2019, a large culvert was put in place on North Creek, a tributary to Drift Creek in the Siletz River Basin, that allows salmon, steelhead, coastal cutthroat, lamprey, freshwater mussels, and other organisms to freely access sixteen miles of stream and wetland habitat for the first time in 62 years.

Contractors removed the old, severely undersized culvert and installed an appropriately sized, open-bottomed structure that doesn’t create a barrier to fish and other animals or to the downward transport of gravel or large wood which improves salmon spawning grounds downstream. The culvert replacement also allows for safe transport to and from popular forest recreation areas and Drift Creek Camp

Other collaborators assisted with funding, including the USFS, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s Fish Passage Program, Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, Oregon Department of Transportation-Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife Fish Passage Program, Trout Unlimited, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, as well as a crowdfunding campaign organized by the Native Fish Society.

Before (1980s)

After (2020)

The follow up

Students in Oregon Coast Community College’s Freshwater Habitats course are assisting in the data collection to determine how the new culvert is affecting the physical aspects of the stream and identify how organisms like salmon and aquatic insects respond to the newly opened channel. Volunteers with Trout Unlimited will continue eDNA sampling at 13 locations in the North Creek Watershed for two more years to determine the presence of difficult-to-survey target species such as lamprey and freshwater mussels. The efforts of these community partners will be complemented by stream temperature monitoring for three years by the USFS and the Environmental Protection Agency. The data resulting from monitoring work is expected to serve as an example for future large-scale aquatic organism passage projects.

OCCC students looking at samples in lab

OCCC students analyzing stream channel

Substrate change surveys

To learn more about this project, check out its coverage in the local news:

For even more nitty, sometimes gritty, details of what occurred throughout the nearly $1 million project’s timeline, click on the buttons below for bi-monthly breakdowns written by project partners as the work was happening:

Yaquina Estuary (Y27)

Reconnecting Tidal Marshes

The tide has large influence on rivers, even miles upstream of the ocean. High tides create temporary aquatic habitats that are extremely important to juvenile salmon and other fish.

Across the Yaquina River from Elk City Road near Cannon Quarry Boat Launch, MCWC and partners improved habitat for coho, chum and Chinook salmon by restoring the tidal marsh known as “Y27”.

Map of the Y27 working area

Y27 at high tide

Y27 at low tide

Contractors removed sections of the failing dike and filled artificial drainage ditches to encourage water to use reconnected natural channels and newly dug channels. We protected spruce trees from a 2001 restoration planting project.

Our crew planted the entire site with spruce and other wetland species and will tend to them over several years to establish forested tidal wetland habitat and control invasive species. Trees and root wads were placed into the channels to immediately provide cover for fish.

As tides carve the channels we started and form new ones, the river will deposit its sediment and actually raise the elevation of the area over time. The new sediment and vegetation will increase the areas resiliency to flooding and sea level rise. This project is informed by the history of restoration on this parcel and estuary science from around the coast.

Funding for this work was received from the Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board, the US Fish and Wildlife Service Fish Passage Program, with additional support from the Pacific Marine and Estuarine Fish Habitat Partnership and the Oregon Wildlife Foundation. Project partners include the City of Toledo, the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Indians, the Wetlands Conservancy, Pacific States Marine Fisheries Commission, Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife and US Fish and Wildlife Service Partners for Fish and Wildlife.

News articles about this project

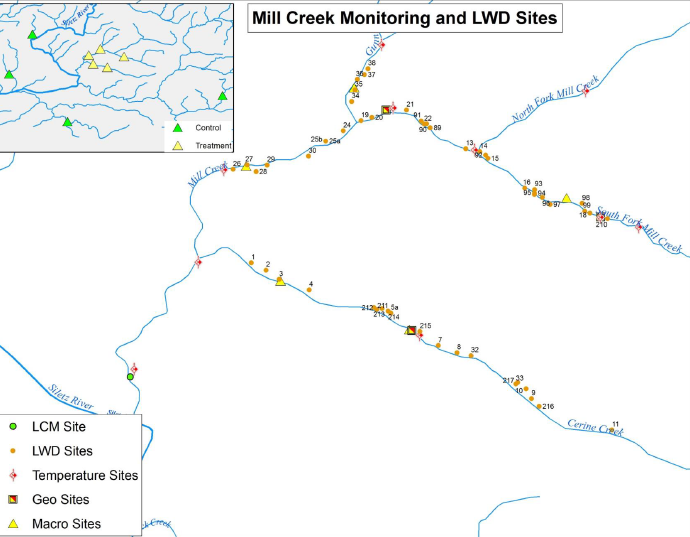

Mill Creek

When large trees fall into a stream, they divert the energy of water and create complex arrangements of pools and riffles that are crucial for young salmon and other animals to survive. Extensive logging and human alteration has dramatically reduced the amount of wood and complexity in streams.

Pool created by large conifer wood placement under an alder forest.

In partnership with ODFW, MCWC installed 679 logs in 6.8 stream miles of salmon habitat in Mill, Gunn, and Cerine Creek. The goal of this project was to restore habitat complexity for young salmon. Large wood accumulates spawning gravel, provides substrate for prey to grow, and creates deep pools and slow water for young fish to live in.

Map of Large Woody Debris sites (LWD), Temperature, Life Cycle Monitoring (LCM), and Benthic Macro Invertebrate (Macro), and geomorphology site (Geo) locations.

Because the mouth of this basin has housed ODFW’s Life Cycle Monitoring (LCM) site for over 20 years, there is long term data about the numbers of juveniles and returning adults in this area. Strong before and after data make this project an excellent opportunity to study the effectiveness of projects like these.

This project is being followed up by an extensive Effectiveness Monitoring project to determine the effects of the large wood placement on fluvial geomorphology, aquatic habitat, benthic invertebrates assemblages, overwinter survival of juvenile coho, and overall coho smolt production for the watershed.

Field tech conducting Aquatic Habitat Inventory study.

Partners include: ODFW, Weyerhaeuser, Oregon DEQ, and OSU College of Forestry. The study is designed to inform future in-stream restoration priorities, large wood placement design, land use management, coastal coho recovery goals and objectives, and limiting factors analyses for coho salmon production.

North Fork Yachats

This project treated approximately 5.5 acres of riparian corridor in the North Fork Yachats Watershed in 2016. Native trees and shrubs were planted and protected from wildlife browse with enclosure fencing. Water bars were installed on abandoned roads to reduce soil erosion and sediment inputs to the watershed, and selected boles of big leaf maple were girdled to create habitat for cavity nesting birds.

Member of our planting crew walking next to planting cage

Buckley Creek

Buckley creek is a direct ocean tributary roughly two miles north of Waldport, Oregon. The creek is occupied by native cutthroat trout, possibly brook lamprey and other aquatic and wildlife species. The site is an important freshwater wetland with beaver pond complexes and a diverse array of habitats. The Buckley Creek watershed area is roughly five square miles.

Previous Federal Emergency Management Agency projects replaced two 48” culverts on Buckley creek in the Silver Sands neighborhood upstream from the project area. These projects left one 48" culvert restricting flow on a private driveway. The culvert underneath this driveway is the last before the stream runs into the Pacific Ocean, just south of Driftwood Beach State Park. The owner dealt with flooding caused by the remaining 48" culvert in any heavy rainfall event.

To complete this project, we paired a willing landowner with an Oregon Watershed Enhancement Board small grant. The culvert replacement was done in late September of 2016, installing a new 84" squash tube culvert to increase wetland connectivity, alleviate fish passage issues and reduce flooding on adjacent properties.

New squash tube culvert providing fish passage at high flows.